Note for Intelligence Memo on Enbridge Proposal for Mainline

I Introduction

The issues of curtailment, pipeline proposals, pipeline apportionment and curtailment are very topical. In simplest terms, apportionment and curtailment are two sides of the same coin. Apportionment is done by Enbridge and reduces shipments to match capacity.

One specific issue is the proposal by Enbridge to change its’ Mainline from a common carrier to a contract carrier (the Proposal). This memo discusses this Proposal.

II Enbridge Contract Carrier Proposal

The Enbridge main line starts in Alberta where it picks up about 2.8 million barrels per day of hydrocarbons (mostly heavy oil) for transport. It travels east and then south into the United States. Enbridge currently operates the Mainline as a common carrier regime. The associated NEB approved tolls are set to expire on June 30, 2021. (see backgrounder on Mainline)

On August 2, 2019, Enbridge proposed to change the main line from 100% common carrier with uncommitted capacity to 90% contract carrier offering committed capacity for a long period of time of up to 20 years. (fn Blakes submission). The remaining 10% would remain as common carrier with uncommitted capacity. Enbridge’s proposal is open for shipper responses until October 2, a process referred to as an open season.

Enbridge has stated that once it has received long term commitments from shippers, it will then proceed to apply to the Canadian Energy Regulator (the CER, formerly the NEB) to have these contracts and associated tolls approved by the CER.

Enbridge has stated that it’s motivation to make this change is due to its canvassing of shippers preferences. If adopted, the main change is to greatly reduce the amount being apportioned. It would also mean Enbridge transfers to shippers the future risk of a reduction in volumes of heavy oil to be shipped in the future. That may seem unlikely in today’s environment of excess production and restricted pipeline capacity, but the world can change. Some oil forecasts predict that demand will drop as renewables increase, which may cause a shortfall in shipments versus capacity ten years from now. If this did occur, the risk of such shortfall would not be borne by Enbridge, but rather by the shippers through their long term commitment contracts.

III Submissions to the Canadian Energy Regulator

A. Opposition to Enbridge Proposal

The reactions to Enbridge’s Proposal have been swift and numerous. In response, the CER asked for submissions to be made before September 5., reply from Enbridge by September 11 and rebuttal from submitters by September 13. More than twenty-five companies, ranging from larger producers, small producers, integrated Canadian producers and pure refiners filed opposing submissions. Suncor has filed extensive arguments on the issue.

B. Supporting and Enbridge Submissions

Submissions supporting the Proposal were received from seven companies (five were refineries or terminal operators in the U.S., plus Cenovus and Imperial Oil in Canada).

C. Legal Arguments from Opponents and Supporters

This dispute between Enbridge and shippers is a big deal between various heavyweights in the Calgary oil patch. Enbridge and Suncor (the most vocal opponent) have engaged the deans of the Calgary regulatory bar.

a). Opponents

Suncor’s opposition is as much procedural as substantive. It objects to Enbridge requiring shippers to irrevocably commit to ship before the CER has decided on the structure. It argues that many shippers do not want to commit now, but are in the position of “sign or die”. It appears that Suncor wants the CER to make an order to delay the open season. The CER should use this delay to decide on whether the Mainline should convert to 90% contract before any shipper is required to commit to become a contract shipper. Suncor also says that the CER has authority to make this order.

b). Enbridge and Supporters

Enbridge submits that the open session should be completed. It will then take the results of the open season, go to the CER before the end of 2019 and ask for approval of the new structure, along with approval of the tolls for shipment. Enbridge argues that any disgruntled shippers can make their arguments to the CER at that hearing. Enbridge also makes the argument that the CER has no power to order the open season to be delayed.

D. Next Steps for CER

(a) Hearing

It is reasonable to predict that once the CER has gathered all this information from shippers and Enbridge, the CER will schedule a public hearing to review the material, make a decision on Suncor’s application and ask each party as to what choice the CER should make. The hearings will likely be well attended by many parties and their legal counsel. The CER decision will have a large effect on the oil and gas industry.

(b) Criteria for Deciding

The CER will have to decide if it will conduct a hearing on Suncor’s application. The criteria used by the CER are more nebulous than the clear black letter law principles used by judges in normal civil litigation. The CER must decide on the merits of the arguments of Suncor and Enbridge based on more general phrases such as “public interest”, “just and reasonable” and generally what strikes them as a better way to determine how the Mainline should be operated.

(c) Possible outcomes

The Enbridge submission notes that 30% of current shippers support the Enbridge proposal and only 20% of current shippers oppose it.

The CER may

- Deny Suncor’s application and have the open season continue until October 2, 2019, or

- Agree with Suncor and delay the open season past October 2. The CER may also order Enbridge to drop the open season requirement that shippers make an irrevocable commitment to ship.

The CER may also ask Enbridge to give all the numbers from their open season. These numbers would include the barrels per day for each shippers that either supports or opposes the Proposal. The CER may also want to know how many of these shippers have indicated that they made a commitment under protest (the so-called “sign or die” group), and therefore wish to see the CER approve structure and terms before making their final decision as to whether to commit.

As part of this, the CER may ask about the identity of the 50% of current shippers that have not made any submission either supporting or opposing the Proposal.

Finally, the other interesting question is, will the CER decide the issue in a way that favours Canadian producers (most of whom oppose) over the U.S. refiners (most of whom support).

IV Consequences if Enbridge 90% Contract Proposal is Adopted

If the 90% contract proposal is adopted, several consequences will occur.

A. Possible Reduction of Shippers Bidding for Committed Capacity

Instead of the current apportionment occurring every month, there will be a one time apportionment at the beginning, which will allocate the 90% committed capacity. By requiring shippers to commit for a long term, it may well weed out the shippers unwilling or unable to do so. If this occurs, it will reduce the number of shippers vying for the 90% committed portion, and therefore reduce the one time apportionment for that capacity. Winning shippers will therefor get a larger proportion of their nominated volumes to be shipped, giving greater long term certainty to both volumes and the tolls per barrel. The remaining shippers that did not want to commit will be apportioned monthly on the remaining 10%, which means apportionment for that 10% piece may be much higher than current 40%.

B. A multi-tiered Structure for Sale of Heavy Oil

The following tiers of producers will form, based on capacity to export and associated costs. It will be like an old-fashioned ocean liner with first, second, third, fourth and fifth class.

- First class will be shippers with committed contract capacity on the Mainline. They will be assured of getting their volumes shipped, and shipped at the lowest cost per barrel.

- Second class will be shippers jockeying for position in the 10% uncommitted portion of the Mainline. They will not be sure of getting all their volumes shipped, but will have the lowest cost per barrel to ship.

- Third class will be shippers that decide to transport by rail. If they have committed rail capacity, they will be sure of getting volumes shipped, but will have a higher cost per barrel to ship.

- Fourth class will be producers that use very expensive capacity such as truck transport. They will not be sure of getting their volumes shipped, and will have the highest cost per barrel to ship.

- Fifth class will be producers that cannot or will not access any capacity for export. They will be forced to sell at the WCS Hardisty price, or to put their production into storage.

C. An incentive to use Committed Contract Capacity to Arbitrage Markets

The creation of the multi-tiered system will also create an incentive for shippers on the committed portion of the Mainline to arbitrage between the price at Hardisty and the price at the Gulf Coast. Normally, market forces do not permit a shipper to make money merely by shipping. The difference in market price of WCS between Hardisty and the Gulf Coast should equal the cost of shipping between those two points. If there were adequate pipeline capacity on the Mainline, this would occur – the shipping cost of $10 per barrel would mirror the uplift in WCS price of $10 per barrel between Hardisty and the Gulf Coast.

However, since Mainline capacity is constrained, some shippers will be forced to use rail, with its cost in the order of $18 per barrel. If one believes that this rail transport will be the marginal cost to get the last WCS barrel from Hardisty to the Gulf Coast, it should set the WCS price discount at $18 per barrel.

This means that shippers with committed capacity will pay a transport cost of $10 per barrel, but gain an uplift in value of $18 per barrel. On other words, they will make a profit of $8 per barrel merely by arbitraging the two markets (Hardisty and the Gulf Coast).

If one believes the above analysis, then this provides an additional incentive for shippers to acquire committed capacity on the Mainline.

V Conclusions

The resolution of how the Enbridge Mainline is operated in the future will have a significant effect on the oil industry in Alberta. Stay tuned as to how all this turns out.

Backgrounder for Enbridge Mainline

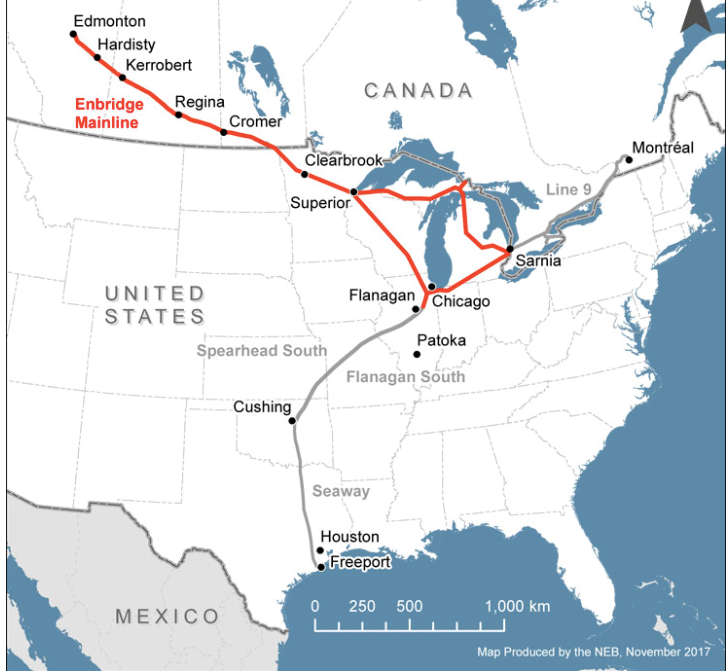

It is important to remember that most of the export of heavy crude from Alberta is done by pipelines. By far the largest pipeline is called the Enbridge Mainline. As can be seen by the map below, the Enbridge Mainline starts in Alberta where it picks up about 2.8 million barrels per day. It travels east and then south into the United States. Volumes are offloaded at various refineries in the U.S. midwest (Minnesota and Illinois in particular). Other volumes move on to refineries in Ontario and Quebec. Remaining volumes are delivered to Flanagan in Illinois. These remaining volumes are reloaded into other pipelines for further shipment into the southern U.S. possibly as far as the Gulf Coast, where many refineries using heavy oil as feedstock are located.

There are many shippers that currently use the Enbridge main line. Some are U.S. refiners wanting to acquire and ship heavy oil to be used as feedstock for their refineries in the U.S. Others are Canadian heavy oil producers who do not want to sell at the Hardisty Alberta price but rather want to move their product into the U.S. and sell at the higher U.S prices. Lastly, there are integrated Canadian producers that want to ship heavy oil to be used as feedstock for their refineries in Ontario, Quebec and the U.S.

Common Carriers Versus Contract Carriers

Pipelines in Canada are either common carriers or contract carriers. The Canadian Energy Regulator (CER, and formerly the National Energy Board before August 28, 2019) is the body that regulates and must approve all aspects of pipelines, ranging from need to build, construction, operation and tolls to be charged to shippers.

A common carrier is open to any person wishing to ship, much like an airline is prepared to sell a ticket to any person walking up to their wicket and wishing to fly. The price of shipping is determined by dividing all costs (both operating and financial) into a cost per barrel cost. which is paid by each shipper for volumes shipped.

A contract carrier requires shippers to enter into long term contracts to ship, much like an airline will charter a plane to one user for a period of time. A contract carrier will require these shippers to commit to ship the contracted volume. Even if they do not ship, they are required to pay the pipeline tariff (a concept known as take or pay).

The CER legislation in effect has a presumption that all pipelines are common carriers (section 71(1) of the old NEB Act). The presumption can and has been rebutted in permit certain pipelines to operate as a contract carrier.

Up to now, the mainline has been a common carrier. All its nameplate capacity of 2.8 million b/d has been uncommitted. Each month, Enbridge announces its available volume and toll for each barrel to be shipped. Shippers make nominations each month as to how many barrels they wish to ship. Enbridge uses these nominations to determine how much each shipper will ship and how much the shippers will pay. The volumes are then shipped, and the shippers pay the tolls. The same process repeats itself in each subsequent month.

In the past few years, heavy oil production has increased and pipeline construction and expansion have not occurred. As a result, there have been more shippers than available volume on the main line. Enbridge has had to use a prorationing process (referred to as apportionment) in which each shipper is only able to ship a portion of their nominated volumes. This process has been subject to much criticism by shippers and has made more work for Enbridge as it tries to make such prorationing system work.

In simplest terms, apportionment and curtailment are two sides of the same coin. Apportionment is done by Enbridge and reduces shipments to match capacity.

Backgrounder for Submissions

Most of the opposition comes from Canadian producers. This may be because many of these Canadian producers are unwilling or unable to make a long term commitment because their future production is not certain. Production may increase or decrease for unforeseen reasons. Some opposition is procedural, and some is opposed to the very concept of contract capacity. They believe that the CER legislation has a presumption for open access to pipelines as a common carrier with uncommitted capacity (section 71 of the NEB Act).

Most of the support for the Proposal is from US refiners and terminal operators that presumably want long term certainty for shipping. These shippers have a greater certainty as to how much shipments of heavy oil they need in order to operate their refineries and terminals. One terminal operator named Ducere is proposing to build a 450,000 barrel per day in Illinois that will permit barge access to the Mississippi river and eventually on to the Gulf Coast. It argues that it needs capacity certainty in order to make this investment.

Suncor has made the most detailed submission on the reasons for its opposition to the current open season. Suncor’s arguments are mostly procedural. It argues that Enbridge is putting the open season cart before the CER approval horse.

It believes that Enbridge currently has unequal market power due to insufficient pipeline capacity resulting in current apportionment. Enbridge believes that Enbridge is inappropriately using this market power to force shippers to commit to capacity before the CER has decided that such a conversion to capacity should occur, or if yes, what percentage should be converted. Suncor argues that current shippers should not be coerced into making a commitment when the alternative is to not commit and lose most access to the Mainline (referred to in submissions as the “sign or die” dilemma).

Enbridge argues that the CER should not interfere in the commercial process of an open season. The open season will gather data as to what commercial support there is for a movement to a 90% contract structure for operating the Mainline. The CER can then use this data when it makes its’ decision as to structure and tolls in a future hearing to be held before the end of 2019. Disgruntled producers can come to this hearing and try to get CER to change commitments

Backgrounder on Linkage to Curtailment and Rail Transport

Curtailment is done by the Alberta government, and reduces production to match the main line shipping capacity, thereby avoiding increases in inventory.

It is logical to conclude that producers who are prepared to obtain committed capacity to move their production may well be the lowest cost producers. Producers that do not wish to make a commitment and instead wish to rely on uncommitted capacity (what some may refer to as the walk up market) may well be the higher costs producers.

Classic economic theory states that efficient markets should cause lower cost producers to continue producing, and higher cost producers should stop producing. If one believes in this theory, one concludes that producers who have committed capacity to ship should not be subject to curtailment for such amount, since they have demonstrated capacity to move such production out of Alberta Furthermore,

the current discussion that suggests the Alberta government should adopt a “rail over curtailment” policy also reflects this concept. If a shipper creates new rail capacity, it should have its curtailment reduced by this amount, since it has demonstrated it is able to move such production out of Alberta.

It may be that the proposal by Enbridge will increase the amount of committed capacity held by producers. This committed capacity will go to the producers that value it the most and are therefore prepared to enter into such long term commitments. They do this presumably because they believe that they are the low cost producers. If this thought is combined with a proposal to not curtail any production for producers that can show such committed capacity, it may be a pathway to an eventual exit from curtailment.