Canada’s Flawed Approach to Provincial Greenhouse Gas Emissions Accounting

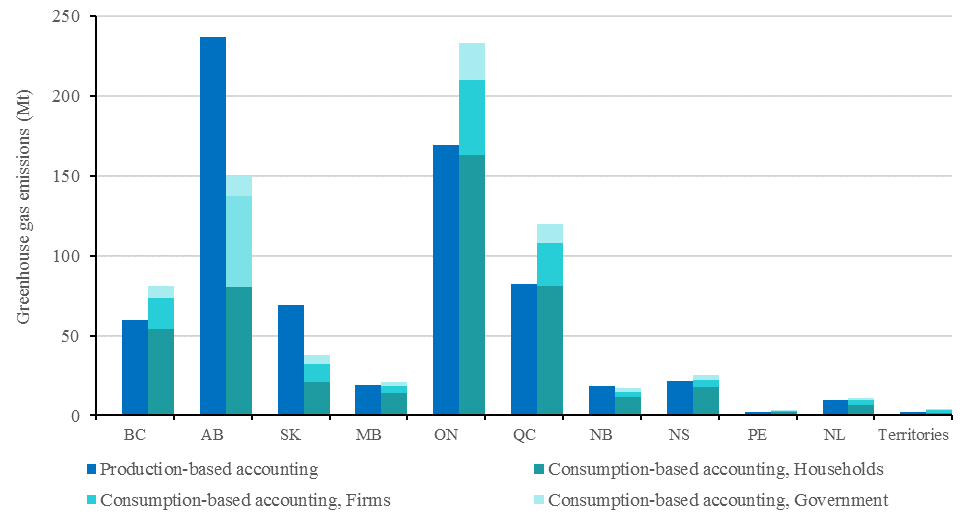

In 2011, Alberta produced 237 Mt of CO2e[*], but was only responsible for the production of 150 Mt of CO2e. By comparison, Ontario produced 169 Mt of CO2e, but was responsible for a much larger 233 Mt of CO2e.

In the world of alternative facts, this may sound like Orwellian doublespeak. I assure you, it’s not. How we assign “responsibility” for emissions has a lot to do with how we measure and record these emissions. At a provincial level within Canada we currently assign emissions using a “production-based” approach. A production-based approach allocates the quantity of CO2e coming from sources within a province’s borders to that province’s emissions account. Above, when I said that Alberta produced 237 Mt of CO2e, that was a reference to Alberta’s production-based emissions account. Production-based accounting is a simple and straightforward way to set up provincial emissions accounts. It also flawed.

There is no denying the relationship between Canada’s emissions and our economy, and a fundamental relationship in economics is that every transaction needs both a buyer and a seller. In other words, a producer and a consumer. Production-based accounting acknowledges the role of the producer, but ignores the role of the consumer.

A recent series of research papers published in the journal Canadian Public Policy and through the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy outlines the calculation of “consumption-based” emissions accounts for the Canadian provinces and territories. Under a consumption-based accounting approach all of the emissions generated in order to produce a final consumption good are allocated to the consumers of that good regardless of the geographic region in which they were produced.

Returning to the numbers presented above, while sources within Alberta generated 237 Mt of CO2e in 2011, much of those emissions were associated with exports to other provinces and abroad. After adjusting for the emissions embodied in provincial exports and imports, the emissions associated with the goods actually consumed in Alberta amounted to only 150 Mt of CO2e in 2011. This is the volume of emissions that consumers in Alberta were responsible for.

Ontario’s relationship is the other way around. Sources within Ontario’s borders emitted 169 Mt of CO2e, but consumers within the province imported significant quantities of goods with high levels of embodied emissions. Consumption in Ontario was therefore responsible for 233 Mt of CO2e in 2011.

There is a fairly consistent pattern across Canadian provinces, with provinces that have high production emissions exhibiting lower consumption emissions (due to the export of emissions-intensive goods to support consumption in other regions) and provinces with low production emissions having higher consumption emissions (due to the import of emissions-intensive goods to support their own consumption).

Source: Dobson, Sarah, and G. Kent Fellows. “Big and Little Feet: A Comparison of Provincial Level Consumption-and Production-Based Emissions Footprints.” The School of Public Policy Publications, Vol. 10:23, September 2017

The assignment of “responsibility” matters because consumption decisions are as important — if not more important — than production decisions.

Consider that Ontario purchasers of natural gas don’t really care where that gas comes from, but they do care about cost. If a policy in Alberta leads to an increase in Alberta’s natural gas price, Ontario consumers are likely to substitute to another source (be it Saskatchewan, B.C. or the U.S.). In this case, even though Alberta’s production-based emissions fall, Ontario’s consumption-based emissions don’t. By extension there is no real change in global emissions, as increases in natural gas production and the emissions associated with it from outside Alberta offset the reduction in Alberta. Alberta’s economy is harmed for no good reason.

This is not just an academic discussion, and it is not just a discussion happening in Canada. At the 2015 UN climate change negotiations in Bonn, researchers indicated that “Countries and individuals can do a better job addressing climate change when they understand the true sources of their emissions” whether these sources are domestic or driven by international trading behavior. (UNFCCC 2015) Consumption-based emissions accounting was explicitly indicated as a potential tool for collaborative cross jurisdictional policy development.

When it comes to climate policy, it’s easy to play the blame game by pointing at high emissions production activities. But if our policies don’t translate to a real reduction in the consumption of emissions intensive goods, we are essentially just paying an economic cost to outsource our production-based emissions, taking these emissions off our own books and adding them to someone else’s. Reductions in domestic production-based emissions accounts may make provinces feel good and look environmentally responsible, but they shouldn’t. The consumption side is an important indicator of incremental emissions reductions and it is a metric that needs a more prominent place in our policy development.

This is one of the key reasons why the use output based allocations (OBA’s) is critical in translating local emissions reductions into global ones. OBA’s create an incentive for firms to reduce the emissions intensity of their output without the loss of export market share. As such, the goal is to lower both the production and consumption emissions without changing trade patterns. For more detail on the OBA mechanism (which has been adopted in Alberta and is a key component of the federal government’s “federal carbon pricing backstop”) see the recent School of Public Policy paper Dobson et. al. (2017).

Sources/Links:

Fellows, G. Kent and Sarah Dobson. 2017. “Embodied Emissions in Inputs and Outputs, A ‘Value Added’ Approach to National Emissions Accounting,” Canadian Public Policy, 43(2): 140-164. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2016-040

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet: A Comparison of Provincial Level Consumption- and Production-Based Footprints.” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 10(23). September.

http://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Bigand-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf.

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Alberta” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/AB-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: British Columbia” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/BC-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Manitoba” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/MB-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: New Brunswick” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/NB-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Newfoundland and Labrador” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/NL-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Nova Scotia” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/NS-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Ontario” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/ON-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Prince Edward Island” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/PEI-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Quebec” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/QC-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Saskatchewan” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/SK-Big-Little-Feet-Dobson-Fellows.pdf

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet Provincial Profiles: Saskatchewan” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper, 9(5). September.

Dobson, Sarah and G. Kent Fellows. 2017. “Big and Little Feet: Full Dataset”

https://www.policyschool.ca/embodied-emissions-inputs-outputs-data-tables-2004-2011/

Dobson, S., G. Kent Fellows, Trevor Tombe, & Jennifer Winter. (2017). “The Ground Rules for Effective OBAs: Principles for Addressing Carbon-Pricing Competitiveness Concerns through the Use of Output-Based Allocations.” The School of Public Policy Publications: SPP Research Paper 10(17)

UNFCCC (2015) “United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Accounting Emissions to Consume with Care” https://unfccc.int/news/accounting-emissions-to-consume-with-care (Accessed May 21, 2018)

[*] CO2e is the conventional measure for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Using CO2e all GHG emissions are converted to a CO2 equivalent measure based on their global warming potentials and then aggregated.